For many of us, fall is a fine

time to plant many perennials. The soil and air are cooler and sunlight is less

intense, so the weather's less stressful for newcomer plants. Competition from

weeds isn't likely to be a big problem, either.

In many of our high altitude

areas, rainfall becomes more regular, too, which helps provide the moisture the

perennials need to start good root growth. Yes, the perennials will soon head

into winter dormancy, but fall planting often gives these perennials a head

start over their spring-planted counterparts.

In spring, the fall-planted perennials should be raring to

grow, larger and more robust.

Prior to planting, you may

want to confirm your local plant hardiness zones and take a look at your local

site conditions to see if you may have some beneficial (or detrimental)

microclimatic conditions that may allow you to utilize better adapted plants in

these areas.

USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Maps

The 2012 USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map

is the current standard by which gardeners and growers can determine which

plants are most likely to thrive at a location. The map is based on the average

annual minimum winter temperature, divided into 10-degree F zones.

If your hardiness zone has changed in

this edition of the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map (PHZM), it does not mean

you should start pulling plants out of your garden or change what you are

growing. What is thriving in your yard will most likely continue to thrive.

Hardiness zones are based on the average annual extreme minimum temperature

during a 30-year period in the past, not the lowest temperature that has ever

occurred in the past or might occur in the future. Gardeners should keep that

in mind when selecting plants, especially if they choose to "push" their

hardiness zone by growing plants not rated for their zone. In addition,

although this edition of the USDA PHZM is drawn in the most detailed scale to

date, there might still be microclimates that are too small to show up on the

map.

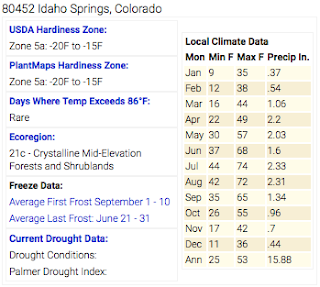

Plantmaps.com is a relatively new reference

website that contains several interactive maps and tools to assist gardeners,

botanists, farmers and horticulturalists. By entering a ZIP code, users can

find not only the new USDA Plant Hardiness Zone, but also the first and last

frost dates, heat zones, drought conditions and annual climatology for their

area, that the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone website does not provide.

Here’s some examples of plant hardiness

zones and climatic data for Idaho Springs, Evergreen, Bailey, and Conifer, and

you will notice that even those some of these areas have the same plant

hardiness zones, they have different first and last frost dates which you

should account for in your plant selection and garden management strategy.

Microclimates

Microclimates, which are fine-scale

climate variations, can be small heat islands—such as those caused by blacktop

and rock outcrops —or cool spots caused by small hills and valleys. Individual

gardens also may have very localized microclimates. Your garden soils could be

somewhat warmer or cooler, or drier or moister than the surrounding area

because it is sheltered or exposed. You also could have pockets within your

garden that are warmer or cooler than the general zone for your area or for the

rest of your yard, such as a sheltered area in front of a south-facing wall or

a low spot where cold air pools first.

No hardiness zone map can take the

place of the detailed knowledge that gardeners pick up about their own gardens

through hands-on experience.

The graphic below depicts the effect of

aspect and solar radiation on soil temperature and soil moisture that can

result in contrasting microclimates on your property.

Many species of

plants gradually acquire cold hardiness in the fall when they experience

shorter days and cooler temperatures. This hardiness is normally lost gradually

in late winter as temperatures warm and days become longer. A bout of extremely

cold weather early in the fall may injure plants even though the temperatures

may not reach the average lowest temperature for your zone. Similarly,

exceptionally warm weather in midwinter followed by a sharp change to

seasonably cold weather may cause injury to plants as well. Such factors are

not taken into account in the USDA PHZM.

All PHZMs are

just guides. They are based on the average lowest temperatures, not the lowest

ever. Growing plants at the extreme of the coldest zone where they are adapted

means that they could experience a year with a rare, extreme cold snap that

lasts just a day or two, and plants that have thrived happily for several years

could be lost. Gardeners need to keep that in mind and understand that past

weather records cannot be a guarantee for future variation in weather.

Other Factors to

Consider

Many other

environmental factors, in addition to hardiness zones, contribute to the

success or failure of plants. Wind, soil type, soil moisture, humidity,

pollution, snow, and winter sunshine can greatly affect the survival of plants.

The way plants are placed in the landscape, how they are planted, and their

size and health might also influence their survival.

Hopefully after

revisiting your local climatic and site conditions you can develop a gardening

strategy that will accommodate these factors.